Can't you feel the rock dust in your lungs?

It'll cut down a miner when he is still young

Two years and the silicosis takes hold

And I feel like I'm dying from mining for gold.

– Mining for Gold, Cowboy Junkies

April 28 has always been a big day in my region. It is the annual day of remembrance for workers injured or killed on the job. Coming from a mining town, April 28 is a day of hard memories — and a time to recommit to making things better.

There aren't very many families in the North who haven't been affected by workplace accidents or death.

My grandfather, Charlie Angus, died on the job at the Hollinger Gold Mine in Timmins. My maternal grandfather, Joe MacNeil, broke his back underground. I had an uncle who died much too young from a brutal form of cancer that was likely due to radiation exposure as a young miner in the uranium mines.

For the longest time, the injuries and deaths were considered part of the cost of doing business. These accidents were regarded as merely personal tragedies.

The longstanding fight to expose the industrial illnesses killing the workers or the monumental battles to improve working conditions and wages has rarely been considered "real history." These struggles were left out of a litany of booster tales by which Canada has told its story of the settlement of the vast northern frontier.

April 28, as a day of remembrance, was first celebrated by the Canadian Labour Congress in 1986. In 1991, the Parliament of Canada officially recognized the day. And now, more than 100 countries around the world mark April 28 as a day of remembrance for workers killed on the job.

But few know the origin of why April 28 was chosen. It is a story worth telling.

To tell this story, you need to know about the town that I live in.

Cobalt, Ontario — no traffic lights, no grocery store, and no hockey arena. There are 1500 people living in little houses perched along the rocky ridges. This is a town of scarred hills, blasted-out canyons, and the infamous "green beaches" where the toxic sludge of over 100 mining operations was pumped into the waterways.

But at one time, Cobalt boasted an extensive streetcar system, eight live theatres, and two semi-pro hockey teams that gave birth to the famous Montreal Canadiens. This little town's unprecedented mineral wealth helped transform Toronto from a provincial town to a global capital for mining investment.

Cobalt was also a place where immigrant families fought with the mine owners over things that today we would take for granted – the right to clean water, the right not to be arbitrarily thrown out on the street and your house or shop confiscated by the mine. It was a town where working conditions were brutal, and those who fought to improve conditions faced firings and blacklisted.

But this is also a story of resistance.

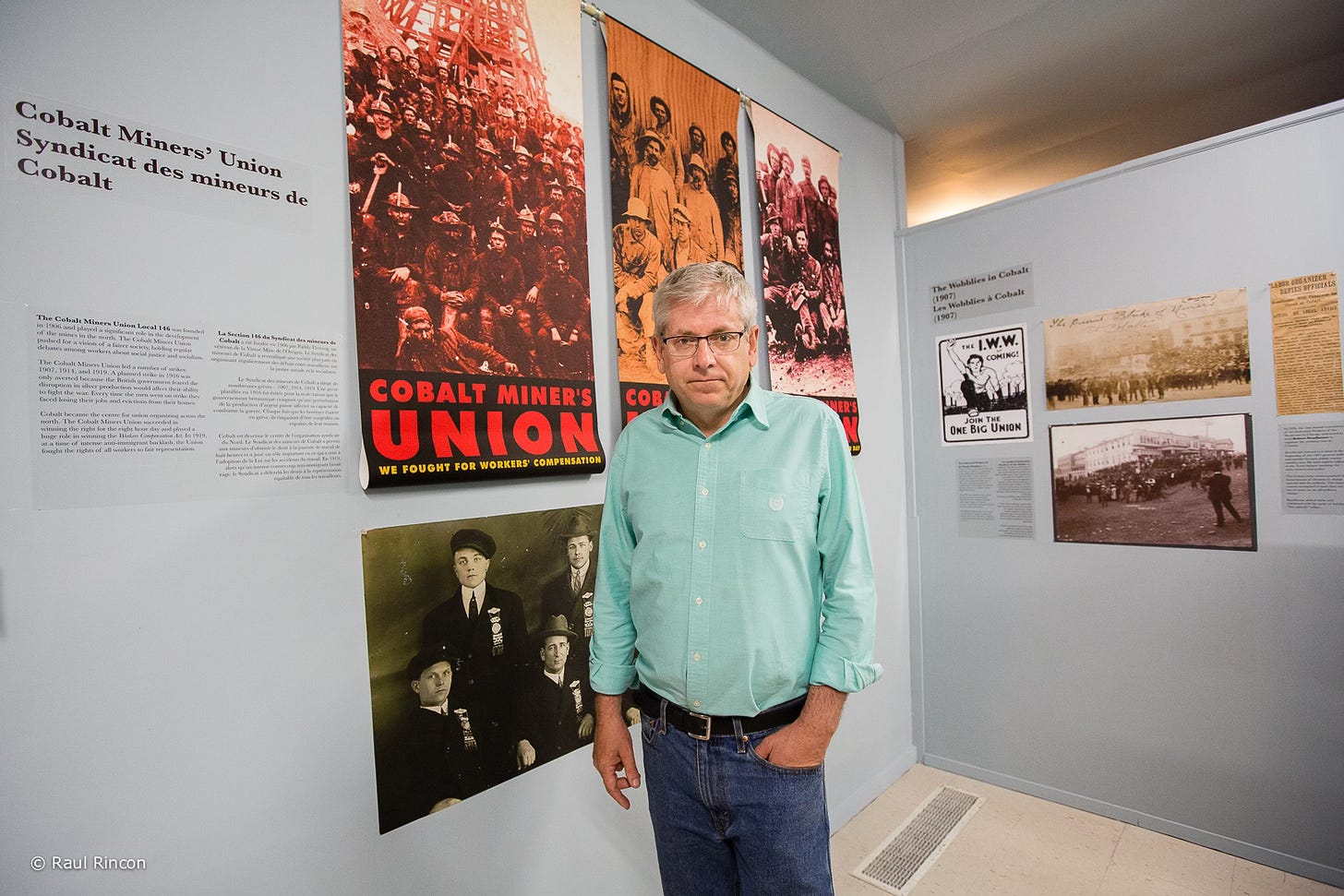

On April 28, 1914, the Cobalt Miners Union, led by Big Jim McGuire, forced the Ontario government to pass the Workers Compensation Act.

For the first time, injured workers would be eligible for pension and treatment. Families of workers killed on the job would have the right to proper compensation.

This was moment that changed everything for workers. It became the principal building block of rights and protections for workers.

And yet, it’s a history that is not taught in schools. And neither is the story of the multiple battles over the coming decades to make workplaces safer, increase wages and ensure people have the right to come home safe at the end of their shift.

This is why April 28 matters.

It reminds us that we stand on the shoulders of giants. It pushes us to do better for this generation of young workers.

I love the history of the North. I have written about Cobalt and the struggle of early working-class heroes like Big Jim McGuire in my book Cobalt: Cradle of the Demon Metals/Birth of a Mining Superpower.

Cobalt was a battleground for multiple visions of how the wealth of the earth could be used and who should be its beneficiaries. Issues of social justice that dominate the discourse today — resource exploitation versus environmental concerns and Indigenous rights, multicultural accommodation versus xenophobic suspicion, the power of the one percent in the face of class resistance — were battled out in the shabby streets of Cobalt.

The economic, social, and political struggles that took place in Cobalt made it a crucible for the Canada that was to come.

These stories need to be told — especially as we face down the oligarchs of today.

Here is a video I made of the story of working-class resistance in the mining camps of the North.

The resistance goes on.

And we are part of it.

Thank you for reading.

You brought a teary-eyed smile to my face today, Charlie. I remember the Cobalt mining museum fondly. The place we took visitors from the south. The place I took my own children before my parents came south. Mining is a way of life - or was up there. There's this feeling underground (I remember vividly from a mine tour during a celebration when I was a kid) that is both sacred and scary. I didn't know that about the Workmen's Compensation Board. But then again, as I am discovering in my research, much of our Canadian history is hidden from us. There are so many stories to be told that just never are as many lie fragmented, undocumented, and untold. Particularly in the northern areas of our country. Thank you for using your platform to tell a few. Today as we head to the polls, we should remember that we are making history just by casting our votes, even if our story is never heard. Let's make it a good act.

Thank you Charlie for not only leading the charge into the election today but sharing the stories of the miners. I knew so little about them but thanks to you I am learning more and more about our Canadian history. ❤️