There was Bogie and Bacall, Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, Nick and Nora Charles, and there was my Dad and Mom.

They were a great couple.

On Friday nights, they would take over the basement of our townhouse in north Toronto and dance to Artie Shaw and Frank Sinatra.

My Dad wasn't like the other dads I knew. He didn't fish or hunt. He never watched a hockey game. He couldn't change a car tire or light bulbs.

He read books, talked ideas and loved to throw a good party.

Growing up, I was a terrible baseball, hockey and football player. I once asked him why our family was so bad at sports.

"When God was giving out eye-hand coordination, the Angus's were in another room getting a drink," he said.

And then he added, "But we can dance."

And he certainly could.

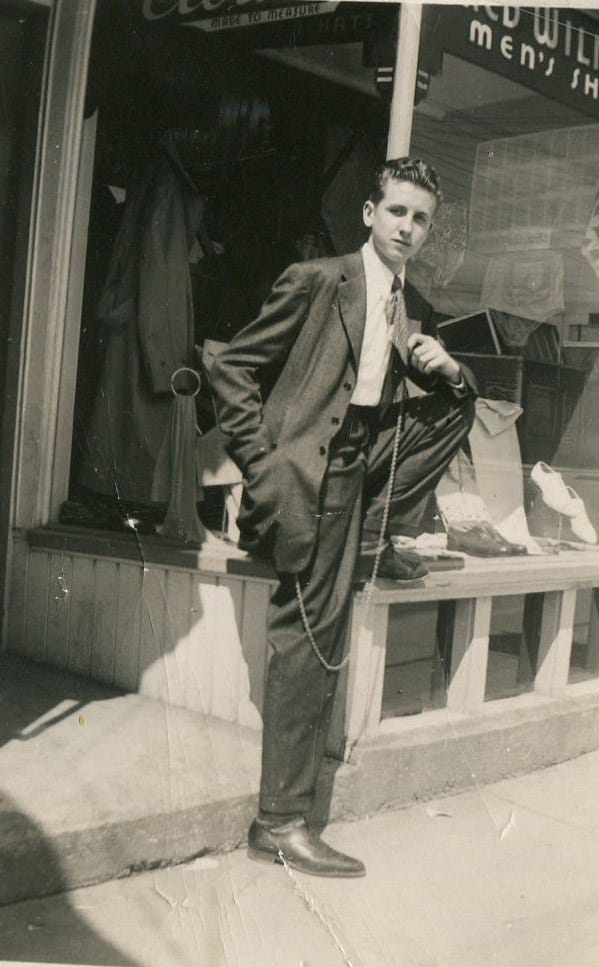

My Dad's claim to fame was that he was the jitterbug king of the old Riverside Pavillion dance hall in Timmins. I still meet little old ladies who tell me about the way my Dad could dance.

The other thing he was really good at was mathematics. In Grade 11, his math teacher came up to him and said, "John, you have a great gift for mathematics. You should quit school and get a job."

That's the way it was in the 1940s in Timmins.

As the son of an immigrant miner, university wasn't an option. Going underground in the mine was the main option. The teacher lined up a job for my Dad selling penny mining stocks at the local brokerage office, and at 17, he went to work (my Mom went to work at 15 at the local telephone exchange).

My Dad grew up in a world of cigar-smoking hucksters selling options on worthless moose pasture as the "next-sure bet" in mining. The brokerage office looked like a horse-betting facility as local folk came in to place bets on rumours and hints passed around the beer parlours of Timmins.

But my Dad was there when the "big one" was found.

In November 1963, his best friend, a brilliant young geologist named Ken Darke came into the brokerage office and said,

"Mark this day down in the calendar, Johnny. We just made history."

Texas Gulf Sulphur Company had hired Ken to look for mineral projects in Northern Ontario. But they decided that there wasn't much future in the north. As the company was pulling up stakes, Darke went rogue and hired a drill crew to test a theory he had about an anomaly in Kidd Township outside of town.

He didn't have permission to be on the property. He had one shot, and in the world of mine exploration, the odds of finding anything were a million to one.

But that single drill hole hit 600 feet of solid copper, unleashing the biggest single day of trading in the history of the Toronto Stock Exchange up to that point. People from all over the world rushed to Timmins to get in on the glamour of a new mining rush. The Kidd deposit was staggeringly rich. It became the deepest base metal mine in the world, reaching a depth of 10,000 feet underground.

I won't get into the circus of what happened in the wake of that discovery. You can read about it in a great new book called Windfall by Tim Falconer.

The short story was that fortunes were made, and fortunes were gambled away. Canada loves its mining booms, as do the hucksters, speculators and fraudsters. Some very powerful people who tried to run big scams in the wake of the Kidd discovery went to jail.

My Dad and Mom had two young children (with a third on the way). They were living upstairs in a small house rented by my mining widow Grandmother. My Dad's father, Charlie Angus, had just died at work at the Hollinger Mine.

My Dad took everything he had and put it down on the once-in-a-lifetime chance. He was not a gambler. But he knew this opportunity would never come again. He made enough money on the play to literally break the bank in Timmins that day — there simply wasn't enough money in the bank to cover the cheque he brought in.

I was a little kid, but I remember the all-night parties and the celebrations that just seemed to go on and on. My Dad's partners went on to make and lose fortunes as they pumped their winnings back into the stock market roulette.

Not my Dad. He pulled out of the lottery and put the money into the dream he had always had – getting an education. He spent years on the road, taking the bus from Timmins to Laurentian University in Sudbury and then to graduate school in Hamilton to earn his degrees.

I remember him coming home on Saturday morning on the all-night bus, totally exhausted from a week at school, only to leave on Sunday evening to take the all-night bus back to McMaster University in time for Monday classes. He penny-pinched every dollar to make things last.

In his 40s, he became a professor of economics and moved our family to a small townhouse in Scarborough. Every cent he made was put away because he promised us that when he was gone, my Mother (11 years younger) would live comfortably.

My Dad drove old beaters and wore cheap suits to work. When the last car died, he just left it in the driveway, where it stayed for years. I don't ever remember him going on a vacation. His idea of wealth was family, and to my Dad, family was an open door.

Having grown up in the multi-ethnic mining neighbourhoods of Timmins, he loved diversity in people. All the strays were welcomed. He welcomed everyone, regardless of their religion, ethnicity, or sexual orientation.

Our table was the welcome place for young gay and punk kids who had nowhere else to go. They were all welcome at the big feasts my Mom and Dad used to hold with lots of wine and singing — especially old Irish and Scottish rebel songs and ballads.

My Dad had an enormous sense of justice. He valued knowledge and had a deep religious faith that wasn't sectarian or judgmental.

Dad never tolerated any discussions around the house that put other people down for who they were or what they believed.

He had little time for the "common wisdoms" of the day. If the pundits and the papers said something was an irrefutable truth, my Dad immediately became suspicious.

He always seemed to be off-side with the latest views and trends. But one thing that never wavered with him was that my Dad believed in justice and people being honourable to each other. It was how he lived his life.

After I was first elected in 2004, he used to call me every morning and every evening. He would get up before I awoke to go through the business and political press, giving me a rundown of what he thought I needed to be aware of in case the media called.

He spent a lot of time breaking down the tax and finance numbers for me because he knew his eldest son just wasn't very good at arithmetic.

He died just before the 2011 election. I have gotten used to him being gone, but I still find myself instinctively reaching for the phone to call him at the end of a long day. There are different kinds of grief, I guess. In the case of my old man and me, it's like the loss of a limb that I continue to try to use years after it's no longer there.

The other thing about my Old Man is that right up to the end he loved a good party with lots of storytelling and as much singing or dancing as possible.

Just before he died, he said to me, "Hey, I hear you and your wife have taken up dancing." I said, "Yah, we have a few moves."

My Dad was never one to boast, but when it came to dancing, he threw down the gauntlet.

"You'll never beat the old man."

He insisted that all the furniture be moved back, and my 80-year-old man and my Mom did the jitterbug in the living room with all of us watching.

"Now top that," he said.

It was such an awesome moment.

My Dad would have loved his wake. It went on all night. The neighbours — Sri Lankan, Jamaican, Italian, Armenian, and Pakistani — came by to pay their respects to "Mr. John." Our family sang and told stories. The only guest missing was him.

But I'm sure he was there as a multi-ethnic crowd in a little townhouse in Scarborough belted out Irish rebel songs at 4 in the morning.

Looking back, I realize that I never said the things I should have said as we sat together in the hospital for those long days and nights. Being of Scottish descent, we just don't say these kinds of things.

If I said anything at all, it may have been,

"Don't worry, Dad, you can go now. We'll take care of Mom."

So, I never did tell him what he meant to me despite the long, slow tick of the clock in the hospital at Scarborough General.

I tell myself now that he didn't need to hear those things. My Dad would have wanted to know that we were going to look after my Mom.

And we did.

Your lovely tribute to your father left me with tears in my eyes. I miss my father. He was the guy who was always ready to help anyone. We have lost so much when we buried that generation.

I bet he was very proud of you.